The FFFEYIBA Project—1990

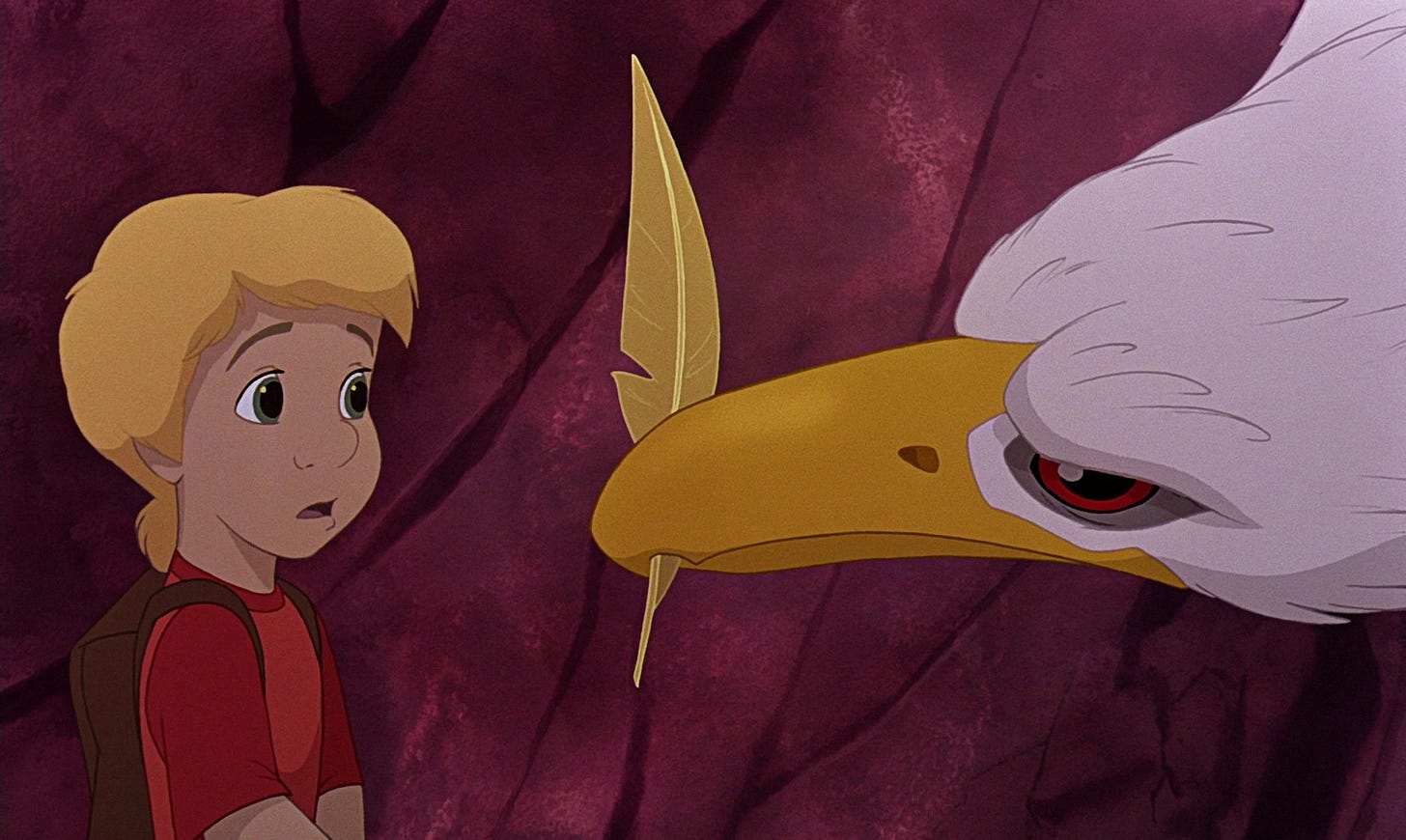

“Animation can give us the glory of sights and experiences that are impossible in the real world, and one of those sights...is of a little boy clinging to the back of a soaring eagle.” — Roger Ebert

For a quick refresher on the purpose (and rules) of the project, see this post.

HM #1: The Hunt for Red October

We’ve got back-to-back Sean Connery awesomeness for the years ‘89 and ‘90, though I think of this one mostly as a feather in director John McTiernan’s cap. He’s surely best-known for Die Hard (and then, probably, Predator), but this one’s my actual favorite from his filmography. A taut, tense action-thriller/political-espionager that takes full advantage of its superb cast, it’s the best of the three adaptations of Tom Clancy’s Jack Ryan material that came out of the 90’s—as well as any other decade subsequently, in my opinion. There’s just something about submarine movies that gets to me every time. Also, Basil Poledouris take his musical contributions to an absolutely elite level. Honorable Mention (HM): I especially love the way the script deals with the problem of the languages, switches from Russian to English in mid-sentence, pivoting on “‘Armageddon,’ which is the same in both languages.”

HM #2: Awakenings

Robin Williams was an extraordinary talent, often finding rich human insights in the zaniest of situations. Tony Zhou, in his wonderful “Robin William - In Motion” video essay, notes that Williams was “a dedicated craftsman who explored how an actor could express character through movement.” For many years, the characters he used to explore and express those things were a bit too wild for me; I had a hard time recognizing the humanity, because Williams’s antics felt so cartoonish. This film, though, changed my mind (along with One Hour Photo). His turn as Dr. Malcolm Sayer is far subtler and vastly more restrained than the work that made him most famous, and shows off an astonishing range and sensitivity that I might not have otherwise recognized. DeNiro got the lion’s share of Oscar attention, but Williams is the one that truly shines. I don’t really think the film “sticks the landing”—not sure it really could, anyway, because the take-away is such a let-down—but Williams is perfect.

HM #3: Miller’s Crossing

I’m not comfortable saying this is the Best Coen Brothers film, because we live in a universe where No Country for Old Men also exists. And because the whole point of this exercise is to get away from “Best” and spend a bit more time thinking about “Favorite” anyway, right? And I am comfortable saying that it’s my favorite. That makes sense, since the time period it’s representing is one also of my all-time favorites (both cinematically and literarily), and the sharpness of the dialogue, the brilliance of the acting, and the masterful cinematography and direction do nothing to dissuade me from my typical affection for the prohibition-noir-gangster genre. But it’s more than just the genre (or the setting), much as I love that aspect of the film. It’s that the Brothers took a dramatically different approach to this one than they did to the quartet of early films that bracket it—namely, Blood Simple, Raising Arizona, Barton Fink, and The Hudsucker Proxy. They played it straight, rather than goofy. I once heard the story—apocryphal, perhaps?—that each actor who received the script read it as a Coen comedy and where shocked to discover that the Brothers meant it to be a drama (with moments of their trademark humor). And that makes all the difference.

Now, for this week’s bombshell…

1984’s Selection: The Rescuers Down Under, by Hendel Butoy and Mike Gabriel

This is my favorite Disney animated film of all time.

Yep. That’s what I said. Favorite. Of all time.

The art style is gorgeous. The technical elements of the animation are superb (and had an enormous impact on other Disney Renaissance films). The music, spectacular. And George C. Scott’s turn as the villainous Percival C. McLeach is just *chef’s kiss.*

It doesn’t really feel like a Genuine® Disney® Animated® Film®, come to think of it. Sure, there are talking animals (though why some talk and others do not is a bit of a mystery), and funny side-kicks aplenty. But there’s no singing. It often feels to be more about it’s setting than its story—Australia is a brilliant setting, I must say! And it’s a sequel (despite Walt’s relentless insistence that his company avoid sequels). In fact, when I look back on it, I see plenty of weaknesses, including the fact that it pretends to be about Bianca and Bernard, and they’re simply not interesting.

On that score, I’ll take a moment to quote John Wright:

The main weakness of the film, oddly enough, is that it is a Rescuers film. The Rescue Aid Society and its two agents, Bianca and Bernard play no role here that could not have been played just as easily by some animals friends of Cody, who has as much ability to escape on his own, with the aid of the eagle, without any mice to help him—or, if a mouse were needed, Jake the Kangaroo Mouse would have been sufficient.

There is much truth in Wright’s criticism—ironically, that the Rescuers are the least interesting part of the film. I think it’s a criticism that applies just as well to the original, actually, which I barely remember (even to this day)…with the notable exception of Brutus and Nero. Similarly, this story’s villain is a much more interesting performance (and character) than the mousy leads, but he’s also a deeply-unpleasant one, and that throws the film’s tonal balance off a hair, shifting us into a somewhat uncomfortable (and unusual) territory.

So yes, I’m aware that there are quite a few reasons why folks have been disinclined to list this one as their favorite. (I think there are a lot of people who’ve forgotten it even exists, in fact.)

But hear me out. The film’s “vibe” is pretty much perfect. The fact that the story’s so frustratingly slight—of secondary importance, even—actually allows the film’s real strength to shine forth: the Australian Outback, and the animals that populate it. Plus, it’s got an absolutely amazing score (from the aforementioned Bruce Broughton). The chemistry between McCleach and…anyone and everyone, actually…is weird and hilarious and memorable. Oh, and it’s got one perfect sequence—a sequence so perfect that I will surely love and defend the film forever, despite any and all flaws its audiences and critics can (correctly) identify.

Nothing Disney had done before (with the possible exception of the Escape from Monstro) or since (with the possible exception of Glen Keane’s work on The Beast) matches the Rescue of Marahute and Cody’s Flight. Absolutely breathtaking.

Take a moment and watch that scene for me, please, if you don’t remember it. It takes place early in the film, so it runs the risk of being forgotten or diminished; of having its emotional impact whittled away by another hour of Bianca and Bernard. But there are few cinematic memories from my youth that I can feel as clearly and easily as this one. It’s so joyful, so exuberant, so overflowing with the energy and excitement of childhood. It’s so beautiful!!

It’s not just that sequence, though. The more I think back on that scene (and on the film as a whole), the more I realize that everything about Marahute is perfect. That character is brilliantly, wonderfully realized; her relationship to her young, to her surroundings, and the the young boy who stumbles into the latter in his attempt to rescue the former and keep them safe is what really makes this one work. Even if we’re not interested in the two characters doing the rescuing—the ones giving the film its name—we’re interested in Marahute being rescued. We need her to be rescued.

I don’t watch The Rescuers Down Under for the mice, really. Or even for the story. I watch it for the eagle, and for the young boy who rescues and befriends her.

I watch it because, deep-down, we all want to fly.