The FFFEYIBA Project—1985

“The world is what you make of it, friend. If it doesn't fit, you make alterations.”

For a reminder on the purpose and rules (and the acronymous absurdity) of the project, see this post.

HM #1: Ran

Remember earlier, when I said that I thought Kagemusha was better than Ran and that it shouldn’t be relegated to “dress rehearsal” status, no matter what critics (and Kurosawa himself) said? Well, that’s true; I said that, and think it. But I also think Ran is a great, great film. So there, and no, that doesn’t make me inconsistent. As evidence of its excellence, our beloved film-whisperer, Tony Zhou, in his (as ever, great) video essay on Kurosawa, “Composing Movement,” highlights four kinds of movement that are found in all of Kurosawa films: the movement of nature, the movement of groups, the movement of individuals, and the movement of the camera. And the castle-burning sequence towards the end of this marathon King Lear adaptation is the most perfect example of all four of those types of movement existing in one jaw-dropping scene. What a master.

HM #2: Brazil

Not all dystopian films grow on me as time wears on. While I am a great fan of the genre, I sometimes find myself distracted by how inaccurate some of them are in the small details of their expected futures, and that distraction hampers their overall impacts (and my suspension of disbelief). With Gilliam’s film, however, I don’t have that problem. I think it’s because Terry’s Future doesn’t seem like it’s trying to warn us of the tech that lies ahead (like, say, a film such as Gattaca). Instead, I think it’s trying to warn us of the pitfalls and problems that we face because we’re humans, not because we’re technophiles. In other words, Brazil feels relevant to me not because it’s correctly predicting the future, but because it’s accurately capturing the present. Sure, it’s an incredibly weird, vacuum-tube-laden present. And who knows what’s happening in some of the dream sequences. But it’s still the present, because who among is is not “caught in the soul-crushing gears of a nightmarish bureaucracy?” Also, the costumes and set design are just stunning. So very, very weird.

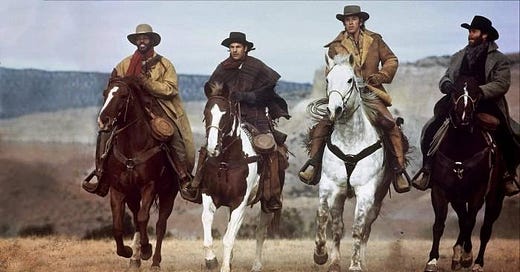

1985’s Selection: Silverado, by Lawrence Kasden

I love Westerns. I love the old-timey, “black-hats vs. white-hats” ones, and I love the Leone-era “everything’s grey and confused and morality’s meaningless” ones, and I love the (sometimes awkward) marriage of the two that seems to be the area occupied by many of the more recent attempts at the genre. Oh, and I really, really love this film, which feels like the cinematic equivalent of old wine being poured out of new wine skins. Old-timey mood and mentality, but with the technical vim and polish of much more recent offerings.

Plus, it’s just so. darn. FUN. I have never come away from a viewing of this film (of which there have been a great many) without a smile on my face.

Here’s how the director’s brother describes it:

Set in the 1880s, the story finds four men headed for the town of Silverado. Thrown together by their adventures on the trail—ambushes, a jail break and posse chase, a wagon train of settlers stranded by an outlaw gang—they try to go their separate ways, especially after they reach the town. But Silverado holds not safety but danger, a threat that only their combined strength can challenge.

The cast is just fantastic. Pretty near my favorite performance from each of the four leads (and definitely my favorite Brian Dennehy performance). Linda Hunt’s Stella is the emotional backbone of the story, and her realization that she is being used by Cobb to keep Paden at bay is one of the most memorable scenes in the film. John Cleese as a British national—“What's all this then?”—inexplicably moonlighting as a small-town, hangin’ sheriff? Sure, why not. The character-acting legend, Richard Jenkins? It’s a small part, maybe, but mighty! And let’s not forget Jeff Goldblum, somehow finding ways to steal nearly every scene he’s in, despite the near universal excellence of the incredibly-likable cast.

The script has a bit of a lull between the time when the four heroes get together and they when actually reach Silverado—the wagon train side story and most things with Rosanna Arquette are the not best parts of the film, by a long shot—but that’s a small complaint in a story that just hums along like a finely-tuned machine. And the quotable lines come fast and furious, including my personal favorite, “Now, I don’t want to kill you, and you don’t want to be dead.” And the action-packed finale is still one of my favorites of all time. Cinematic comfort food, truly.

Paden wears a black hat, though. So maybe there’s some new wine in the skin, after all.

Let me make quick mention of what I consider the film’s most-transcendent element: its absolutely perfect score, from Bruce Broughton. One of the truly great Western scores, with a spectacular, Elmer Bernstein-esque theme and never a dull note. (Broughton himself has been very public in discussing Bernstein’s influence on his composition, which comes as a surprise to absolutely no one who loves Westerns and their music and has seen this film and The Magnificent Seven.)

Still, despite all the fun—and there is fun aplenty running through each and every of the film’s 133 minutes—it hits as hard (and for the same reason) as any great Western. On that matter, I’ll let Mark Kasdan have the final word:

Good and evil existed in the Old West, of course. But we care only because they also exist today. The Western hero is a compulsively watchable figure, timeless despite his cowboy gear. He confronts for us the choice that can be honorable or not and shows us how to comport ourselves in the extreme circumstances that frighten and fascinate us. It gives us pleasure to watch him ride fast and punch hard and, if necessary, shoot straight. But he lives on because it gives us something we need more than pleasure to watch him live gracefully and act honorably and, if necessary, die bravely.