Three Reflections Upon Watching Nolan's Interstellar Once Again

"Interstellar has a mystical strain, one that's unusually pronounced for a director whose storytelling has the right-brained sensibility of an engineer, logician, or accountant." — Matt Zoller Seitz

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

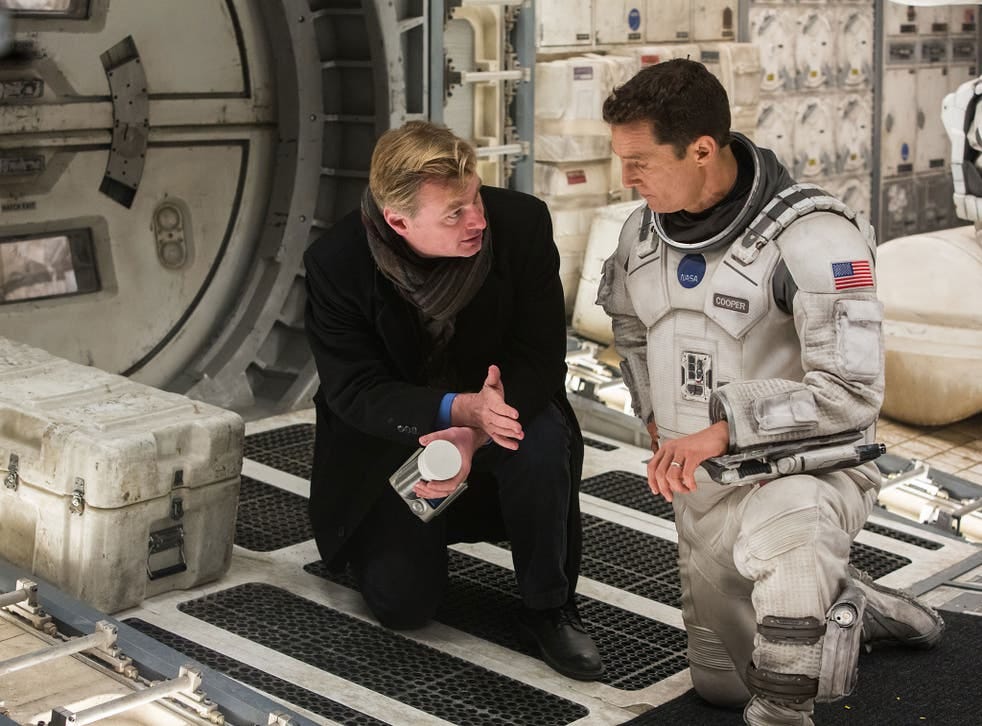

“The last act does not work:” I love Nolan. I’m fascinated by his relentless obsession with time and memory and truth, and I love to watch the warp and weft of those ideas throughout his films, both individually and in his filmography as a whole. I consider him unique in the world of modern film—unique, perhaps, in the history of the medium—in his extraordinary ability (and even more extraordinary desire) to combine the simplicity and vigor and scope of a populist’s palette with murky, often-impenetrable esoterica and absurd(ly) high-concept premises. He’s making “Four-Quadrant Movies,” but on his own terms; he’s giving the people what they want (mostly) and doing what he wants (mostly), all at the same time. I love the audacity of his ideas, the precision of his craft, and the confidence of his direction. And as I remembered while rewatching it again for the 4th or 5th time, I love Interstellar.

…which is why it particularly pains me to say that the finale of this idealistic, extravagant, wildly ambitious space odyssey (or should that be “space Odyssey?”) simply does not work for me. Not at all.

I think I understand what Nolan’s trying to do in the film’s finale(s), and if I’m right, then I love it. But I can’t escape the feeling that he’s set himself an impossible task. The point he’s trying to underscore—the surprisingly-revolutionary notion that love and affection (especially between parents and their children) is among the universe’s most powerful forces and we ignore it at our peril—is simultaneously true and reductionist and important and absurdly hokey and profound and impossible to represent visually in a way that makes any sense or is remotely interesting.

“Love is the one thing that transcends time and space; maybe we should trust that, even if we cannot understand it,” says Hathaway’s Amelia Brand in the film’s early going, and the “payoff” for that claim is hanging, Damoclenian, over the film’s head for much of its remaining runtime. But when that payoff finally arrives, I don’t think it can be described in any other way than as a disappointment; a dramatic letdown. At its most fundamental, most cinematic level, the Library Tesseract sequence is bland and confusing, and while the latter characteristic has always been a (beloved) Nolan hallmark, the former is wonderfully rare in his films.

And utterly deadly in this one.

“The failure of the last act is felt all the more since the middle is so mind-blowing:” Once we’ve waded through the (obligatory, in Nolan films) exposition of the first act, where his characters wordily explicate the scientific ground rules, the near-impossible problem Cooper’s trying to solve, and the emotional and physical conflicts that will stand in his way, we are given some of the most imaginative, most visually and emotionally transcendent filmmaking found in the entirety of Nolan’s filmography.

The water world (Miller’s Planet) is a wonderful physical space, and shot in such a way that it reveals its mysteries and dangers to the film’s protagonists and its audience at nearly the same time. There’s some wonderful action-as-character development (including some exhilarating moments with the robot CASE). We realize that the reality of relativity’s “time slippage” is far more devastating than we could ever have imagined when we were grappling with the theory during the film’s dryer expositional sections: “We’re stuck here till there won’t be anyone left on Earth to save.” “I’m counting every second, same as you, Cooper.” And the mountainous, inexorable waves are some of the most terrifying things I’ve ever seen.

Plus, the use of music is pitch-perfect, both intellectually—each tick in “Mountains” is an hour on Earth—and on a visceral level.

The ice world (Mann’s Planet) is an equally impressive space, though the exhilaration brought on by the planet’s stark and wondrous “mirror” icescapes quickly succumbs to the ominous threat its inhabitant poses to the successful completion of the Lazarus mission. The false dichotomy that Mann (and Brand) present—their stubborn insistence that Cooper must choose between the heroism undertaken for love and that exercised for the sake of our race’s survival—is heartbreaking and wrong-headed. We do things for the good of the race because it is made up of individuals we love, not in spite of that fact.

The revelation that Mann’s motivations are so deeply flawed and self-centered is devastating, but unsurprising; his betrayal, all the more painful because his humanity and the suffering that comes from it are so evident, despite the man’s attempts to suppress both as dangerous to humanity’s survival. His reaction when Cooper awakes him from his long, Lazarushian sleep is one of the film’s most poignant moments: “Pray you never learn just how good it can be to see another face.”

The fact that Mann cannot live up to the icy detachment he preaches tells us a great deal about him, perhaps. But it tells us even more about the ideals he and his unreliable mentor have embraced. Man is not meant to operate alone, Godlike, setting himself above “ordinary” human emotions. These emotions are not what make us weak and ineffective; they are not a threat to our humanity. They are our humanity.

And then, of course, there’s the docking sequence. Perfectly paired with Zimmer’s astonishing score, which makes such wonderful use of the earth-shaking sound of the Harrison & Harrison organ in London’s Temple Church, it is beautifully and utterly overwhelming. It was one of those mind-boggling set-pieces that only someone as inventive and audacious as Nolan could imagine. I remember watching this film in the theater when it was first released, and marveling at the way in which everyone’s head moved farther and farther to the side during that scene, the entire audience mirroring Cooper’s own body language as he battled to return to the ship—again, shades of Odysseus. (This time around, I was particularly struck by the ironic insignificance of Mann’s comeuppance. For a man who cloaks his selfish actions in the guise of , there is nothing quite so incongruous—nothing quite so petty—as his final monologue, cut off in the midst of his pitifully unconvincing justifications.)

To top it all off, we have the sacrificial misdirect and descent into Gargantua, harkening back to Wayne’s actions in The Dark Knight Rises. Which also saves Hathaway, come to think of it. (Another parallel? The utter rejection of the notion of “The Noble Lie.” Few films are as deeply committed to the power and importance of the adamantine truth as Nolan’s.)

“Thomas’s villanelle is the perfect anthem for Professor Brand. Oh, and it’s awful:” The only thing more powerful than my hatred for Brand’s use of “Do not go gently” is my love for how thoroughly and movingly Nolan (through Cooper) slaps it down. Now, in fairness, I’ve never liked that poem. It’s always felt angry and bitter and hopeless to me. And that’s exactly why it works so well for Brand, I suppose. He is a man without hope; a man whose primary emotion as he experiences the inevitable loss of power that comes with old age is rage. The fact that he’s overseeing mankind’s loss of power at the same time as his own makes him think the poem even more relevant. In truth, it is deeply wrong in either case.

The day is closing for us, perhaps, but it is only the fragmentary individualism of Brand (or Thomas) that makes us think our light is going out. We parents do not grow weak in our old age; we transfer our power—our undying light—to our children, increasing it exponentially by pairing their youthful optimism and passion with our knowledge and experience. In the film, Cooper is the catalyst for mankind’s salvation, but it is Murph that brings it to pass. As Nolan(s)’s script says, parents exist “to be memories” for their children. The remembrance of one’s parents provides us with the impetus and focus necessary for the actions we undertake, but that force is directly tied to the deep emotions their fading—their going gently—stir up in all of us. That’s hardly hopeless or angry or bitter, though; memories are tremendously powerful, as is the love that they bear.

It’s one of the film’s most bittersweet touches that Cooper’s story is at such odds with the point it’s making. The sadness of the film’s finale is not that he just a memory to his daughter, but that it’s very nearly the other way ‘round. He’s a man outside of time, a Lazarus raised from the dead who has come to regret his own resurrection. And as Murph gently reminds him, parents are not meant to watch their children die. That’s a thing that leaves one powerless—raging and raving against the dying of their light, rather than your own. Man must pass his place and his power on to his children, and he recognizes that as both inevitable and good.

Mankind survives because parents love their children.

“We’re just here to be memories for our kids.”

This is a wonderful treatment of one of Nolan's masterpieces. I do have to say, however, that "Do Not Go Gentle" is one of my favorite poems.