The FFFEYIBA Project—1986

“What is art? ...a declaration of love: the consciousness of our dependence on each other. A confession. An unconscious act that none the less reflects the true meaning of life—love and sacrifice.”

For a reminder on the purpose and rules of the project (and an attempt to justify the insane acronym), see this post.

HM #1: Hoosiers

Gene Hackman was one of the greats. While this (eventually) legendary underdog film is not my favorite of his projects (because let’s not forget that The Conversation exists, for starters), it is probably the one that I find the most straight-up enjoyable to watch. Looking over his filmography, it appears that Hackman wasn’t much for the “feel-good.” But when he did it, he showed himself the master there, as well. His Norman Dale is a real treat (even if production was not). And who doesn’t love a film that’s 73% training montage, set to Jerry Goldsmith’s spectacular score? “The Pivot” track is probably my personal favorite; it’s the drive (and the hint of Copland) that gets me, I’d guess. Brief Note: Does the fact that Jerry wrote the music for both Hoosiers and Rudy make him the master of the Feel-good Sports Underdog Theme? Probably; probably.

HM #2: Castle in the Sky

Sometimes known as Laputa (which reminds us that there are some interesting connections between it and Jonathan Swift’s world of Gulliver), this was the first Studio Ghibli film, and features a great many of the hallmarks of Miyazaki’s later works, such as his ever-present theme of nature vs. technology. Oh, and flying. Dola and her gang of sons are hilariously and memorably goofy—perhaps I was wrong to call Lupin III an outlier in that regard—and this film’s Magic Girl puts on as dramatic an appearance as in any of his film. But the truly memorable bits are Hisaishi (which can be said of nearly every Ghibli film) and the robots. Who can forget those robots? Those fabulous, fabulous robots, known to have influenced such films as WALL·E and The Wild Robot. Oh, and Atlantis: The Lost Empire. (And to have been influenced themselves by Fleischer’s “Mechanical Monsters.”) Brief Note: Speaking of magical girls, Atlantis’s magical girl is Princess Kidagakash, shortened to Kida. Laputa’s magical girl is Sheeta, and she’s a princess, as well. Mere coincidence, surely.

HM #3: Aliens

This is one of the (truly few) truly great sequels, because it so utterly reinvents what came before. Trying to out-Ridley Ridley Scott’s Alien would have been a fool’s errand (though David Twohy gave it a go), but Cameron goes off in such a dramatically different direction that our natural inclination to try and compare his film to Scott’s falls immediately by the wayside. In fairness, I’m sure at least a bit of my appreciation is that it’s just a better fit for me personally. I really don’t like horror movies or jump scares (and the former is basically what Alien is, and it’s got some of the most famous instances of the latter ever. Action, on the other hand, is always a blast, and Cameron is among the greatest directors of action ever. When this film was voted the “42nd Greatest Film of All Time” by Entertainment Weekly, they called it the “greatest pure action movie ever.” George Miller’s probably messed with that claim a bit in the years since, but gosh, James can do action. (Now, if we could just convince him to never, ever, ever try writing a single line of dialogue again, we’d be all set.)

OK. Time for 1986.

1986’s Selection: The Sacrifice (Offret), by Andrei Tarkovsky

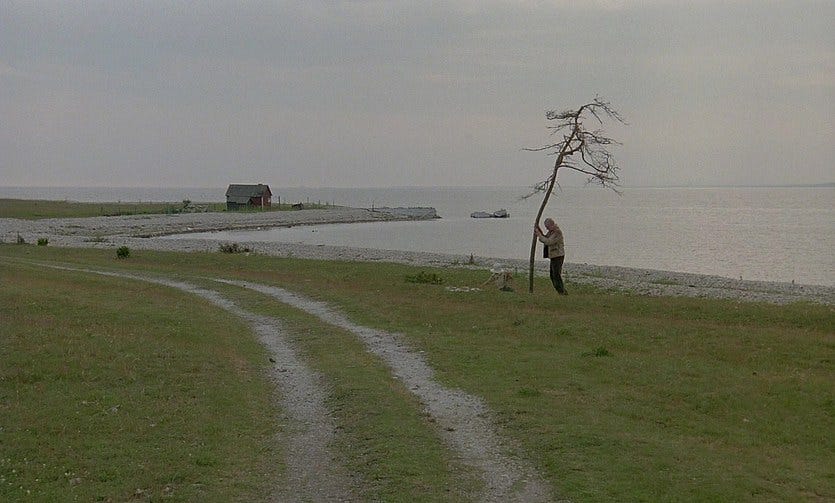

The image at the top of this piece is my laptop wallpaper.

Take a moment and look at it again, please.

It’s astonishing, isn’t it?

Perhaps just as astonishing, I find myself thinking about Tarkovsky’s masterful Offret multiple times a week. Not because it’s my wallpaper, but the other way ‘round. Long before I decided to make this frame the thing I saw each time I booted up my computer in the morning—a stunningly powerful image from an even more stunning, emotionally devastating shot—I was consumed by this film to an astonishing degree. At the most unexpected of times and in the most unexpected of places.

It’s never been relevant to my life (thankfully), yet at the same time, it has always felt like it was. And I have probably spent more time dwelling on this film’s themes and message, its images and sounds, and the sheer (subdued, but immensely powerful) audacity of its artistic vision than I have on those of any other film.

I can’t get it out of my head.

At the dawn of World War III, a man searches for a way to restore peace to the world and finds he must give something in return.

It’s a film that defies explanation, as do so many of Tarkovsky’s works. There is an etherial, floating quality to its actors’ movements and its images that hypnotizes the viewer, even while the weight and density of its philosophical conversations threatens to drag that same viewer downwards. The dichotomy is impossible, and perfect.

It challenges and it bewilders; it inspires and confounds; it transports, it questions, and it haunts. It makes such spectacular use of image and music—including an absolutely shattering use of “Erbarme dich, mein Gott” from Bach’s St. Matthew’s Passion—that it leaves one breathless, with a finale that stands as one of the most moving things I have ever experienced.

It’s not always easy to understand or to clearly explain what it means to say that “cinema is art,” but this is art; true and towering. Or else, nothing is.

Erbarme dich, mein Gott,

Um meiner Zähren Willen!

Schaue hier, Herz und Auge

Weint vor dir bitterlich.

Erbarme dich, erbarme dich!Have mercy, my God,

for the sake of my tears!

Look here, heart and eyes

weep bitterly before you.

Have mercy, have mercy!